For Nascent Science Fiction Readers, A Primer

Wherein I give you a reading list.

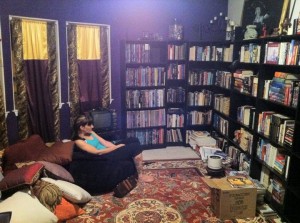

While I will read everything once, there are things I will not read twice. For instance, the works of Ayn Rand (shrill satanist screeds masquerading as “feminist” philosophies) or the over-hyped Illuminatus Trilogy (which boils down to a 3,000 page practical joke on the reader) will never grace my bedside table again. However, the books remain loved because they are books, and have a place within my library.

From time to time, someone new to the genre of “science fiction” will ask me for recommendations. “What’s good?” is a common question, followed by “What should I read?”. A difficult question. Science fiction is rarely about “the future.” These stories are typically metaphors for social issues that we, as a species, are facing now – just wearing clothes that have yet to be invented.

The following is a list for nascent science fiction readers.

It is in no particular order. Works were chosen for several reasons. Some because they are exceptionally influential in style, spawning new sub-genres. Others because they are simply well-written. Others because they are fun. I have included some notes that I hope will be helpful.

The Demolished Man, Alfred Bester, 1952

Alfred Bester is one of the greatest tragedies in the history of sci-fi. He is an unsung master of the genre; few people know of his existence or his stories but everyone has been exposed to his ideas. In much the same way that Citizen Kane changed cinema, Bester’s works changed speculative fiction. The Demolished Man asks a simple question: In a world where people can read thoughts, where criminals are apprehended before their crimes are committed, how does one commit murder?

A Canticle for Liebowitz, Walter M. Miller, 1960

Another “lost” author, Walter Miller wrote two novels – Canticle in 1960, and a sequel that he died finishing (Saint Liebowitz and the Wild Horse Woman, 1995). Miller finished Canticle, won several awards for it, and promptly vanished from the writing scene for 35 years. A Canticle for Leibowitz is a post-apocalyptic story about how the Catholic church strives to retain human knowledge after a nuclear holocaust. I sometimes think that this story drives a large part of my dedication to the mission of Wikipedia.

Schismatrix, Bruce Sterling, 1985

In 1985, the sub-genre of cyberpunk was being invented. Schismatrix is, in my opinion, Sterling’s magnus opus: it is a story about a future war between two factions of posthumans: shapers (those who are genetically modified) and mechanists (those who are bionically augmented). There exists a “special edition” of the book entitled “Schismatrix Plus” which includes the core novel as well as several short stories that take place in the same universe.

Dune, Frank Herbert, 1965

Dune is a story that is many things to many people. Primarily, it is a discussion about politics and the philosophy of, and how economic scarcity affects social change.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Robert Heinlein, 1966

Heinlein was one of the masters of science fiction. Sadly, as his health deteriorated, his writing became . . . erratic . . . in quality and metaphor. Harsh Mistress, however, is a wonderful space adventure. Its science is, quite simply, bad – but Heinlein never really cared about that as much as he cared about describing esoteric societies. In this case, he deliberately chose the harshest environment he could imagine a society thriving and wrote about it. It is a fun read.

The Diamond Age, Neal Stephenson, 1995

Stephenson has been criticized by many (myself included) that his endings are flawed. However, the end is not the beginning or the middle. This story is about an experiment: can free access to knowledge change a person’s life? Is education a silver bullet, the way to effect true social change? To say nothing of the neat ways he uses the idea of nanotechnology.

Stranger in a Strange Land, Robert Heinlein, 1961

Master Heinlein’s second entry in this list. Many people assume (incorrectly) that Heinlein was a rabid conservative, bent on social fascism. Nothing could be farther from the truth: he wrote about stories that would piss people off. Stranger in a Strange Land is the exact opposite of right-wing ideals; the hero of the story is a poly-amorous hippie, a “Tarzan” raised by Martians. I will say that Stranger does a lot towards cementing his reputation as being hyper sexist.

The Number of the Beast, Robert Heinlein, 1980

Heinlein’s final entry on this list is the story in which he explores the idea of alternate dimensions and universes. The title of the book takes its name from the number of known parallel dimensions: six to the power of six, to the power of six. It is a fantastical yarn, and one that isn’t particularly well-written – but its influence has been massive.

Neuromancer, William Gibson, 1984

Neuromancer is but one part of Gibson’s famed “Sprawl” trilogy. It is a dark work, often confusing, and written as if the reader is a contemporary. It, too, is excessively influential, and can be considered the progenitor of modern science-fiction.

A Scanner Darkly, Philip K. Dick, 1977

This is a story about drug addiction. At its core it asks questions about what “identity” actually means. It’s a dark story, all the darker because of a heavy injection of autobiography.

Cat’s Cradle, Kurt Vonnegut, 1963

A darkly humorous satire, Cat’s Cradle pokes fun at religion, the nuclear arms race, and our inevitable technological apocalypse. Vonnegut earned a master’s degree in anthropology for this work. Its an easy read and well worth your time.

The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin, 1969

Le Guin is probably the master feminist writer in science fiction. It is a story about sexual identity precisely because the inhabitants of one of the worlds do not possess gender (save for a short period once a month).

Always Coming Home, Ursula K. Le Guin, 1985

A difficult book to locate, Always Coming Home tells less of a story and more of a way of thinking. Like most of Le Guin’s works, it is heavily focused on Taoist philosophy. She refers to the work as “future archaeology,” and many people will say that it is not science fiction. I am willing to engage in fisticuffs with those people.

Rendezvous with Rama, Arthur C. Clarke, 1972

Clarke’s works are classically “hard” science-fiction. They are often thin on overall plot but extremely thick with atmosphere an potential. Clarke is at his best when he explains very little and leaves the reader to ponder the vastness of space. Rama is a perfect example of this. Clarke would later revisit the world of Rama with three additional sequels (written with the help of Gregory Benford). A word of warning: either read Rama and quit, or read them all.

Comments on For Nascent Science Fiction Readers, A Primer

HOLY FUCK!

it is very rare that I totally agree with anyone. Thank you.

I have a garage sale copy of “Always Coming Home” on my bookshelf, I think. I’ll have to move that up my reading list. My favorite Le Guin novel is probably The Dispossessed, but The Left Hand of Darkness is the obvious most-classic of her classics.

What started it it for me was definitely Asimov, specifically the Foundation series.

I still have much love for C.S. Lewis’s The Space Trilogy. Best appreciated in conjunction with the album The Monster Who Ate Jesus, by Blaster the Rocket Man.

One of my super favorites is the Cities in Flight set by James Blish.

I think Stephenson’s Anathem makes a nice follow-up read to A Canticle for Leibowitz.

Spin by Robert Charles Wilson is really good.

Some of the pre-1950s classics ought to be on any new sf reader’s list as well: Brave New World, and a smattering of the most-adapted early H. G. Wells novels, like The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds.

And I’d add a Singularity novel or two into the mix. My pick would be A Fire Upon the Deep by Vernor Vinge.

Anathem is a fun read: http://www.gaijin.com/2008/09/anathem-a-discussion/

Le Guin, for me, is mostly about the Earthsea trilogy. But that’s me; less sci-fi there, more Taoism.

Yeah, Earthsea is brilliant. I didn’t mention that cuz, yeah, not sci-fi. Sadly, I didn’t read any Earthsea until I was an adult. Hopefully I can keep Brighton from that sad state of affairs.

“the bloated child of A Canticle for Liebowitz and Plato’s Theaetetus.” Hah! Perfect!

The copy of Always Coming Home I have came with an audiocassette of the songs of the Kesh- I should probably find someone with a USB-capable cassette player and throw that one in there, shouldn’t I.

I read quite a bit and I don’t remember anything. Not the plot, hardly the characters, and definitely not the trivia. It makes for interesting re-reads, I can reread Agatha Christies without remembering who killed, and enjoy the plot like the first time.

However, I remember, always, the way a book made me feel. I am a fantasy gal myself, rather than Sci-Fi, but I read The Left Hand of Darkness and it felt good, I rememeber it as one of the best books I’ve read. I never really followed suit on Sci-Fi. But I read Earthsea, and I loved it too.